Most blog posts suffer from the same problem: they feel like content marketing. The reader is never allowed to forget that what they’re reading is, first and foremost, a marketing asset.

This is sometimes caused by an obvious misstep, like a ham-fisted product reference or an out-of-place call-to-action. But most of the time, the signs are subtle and more insidious, providing a glimpse through the masquerade to the sales engine underneath.

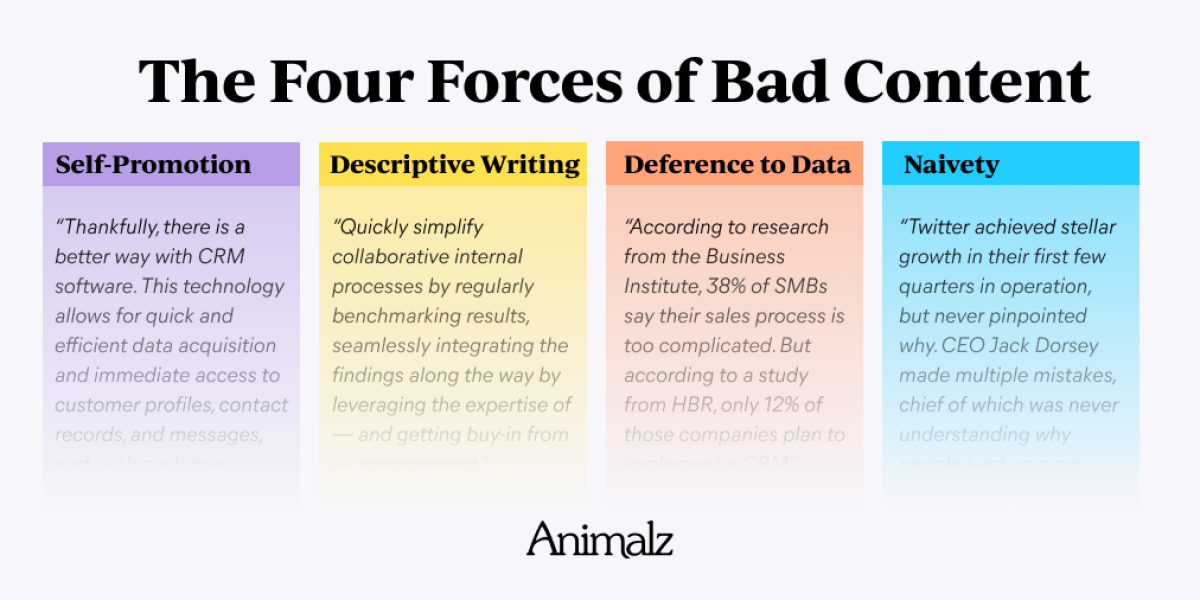

These signs—unexpected self-promotion, descriptive writing, deference to data, and naivety—create friction between reader and writer, and they ensure that the audience always feels, in some small (or large) way, sold to. Together they make up the four fundamental forces of bad content.

1. Unexpected Self-Promotion

“Thankfully, there is a better way with CRM software. This technology allows for quick and efficient data acquisition and immediate access to customer profiles, contact records, and messages.”

The core challenge of content marketing is making sales easier without alienating the reader by obviously selling to them. Attempts to reconcile these two goals often lead to helpful articles becoming undermined by product calls-to-action and thinly veiled sales pitches in places where they don’t belong:

There’s the “product shotgun” strategy where CTAs are blasted into every inch of available whitespace: after the fold, before the conclusion, between paragraphs. This is unpleasant but obvious—like a salesman with a foot in the door, it’s easy to recognize their unwelcome effort and say “no.”

There’s the bait-and-switch “I’m 800-words in and forgot to mention the product” approach, where the final paragraph is given over to a grotesque and unsubtle product showcase, souring the reader’s final moments with your article.

There’s the insidious “undercover agent” tactic, where the writer talks about their product in the abstract (like the example sentence above), believing that the reader won’t realize they’re being sold to.

But readers are smart. They don’t like being sold to, and they especially dislike being lied to. But it doesn’t need to be so adversarial.

Write About the Problems Your Product Solves, Not the Product

When an article bludgeons the reader with the features and benefits of a product, it feels like you’re being sold. But when the article helps you solve hard problems in a new way, and the product naturally emerges as the conduit for pursuing that new way, then the idea to try the product is effectively “incepted” into your brain. You want to try the product, and you feel like you arrived at the decision under your own steam.

Any article about “automating UX research systems” needs to contain some generalizable framework or methodology to help the reader, you guessed it, automate their UX research—regardless of which platform or tool they use to do so. But read that article on the Airtable blog, and the reader can’t help but recognize that Airtable can probably help with those processes.

Remove the product from the article, and it still provides value: the product is a welcome side dish to accompany the main meal of whatever new process, perspective, or framework your article shares.

Set Expectations From the Outset

When you do want to mention your product, do it openly, honestly, and intentionally. Instead of sticking product references into blog posts after the fact, focus on writing blog posts that naturally segue to your product.

After all, there are many topics that require product mentions—it would be weird to write an article about “heatmapping” without mentioning Hotjar. Wildbit managing editor Dr. Fio Dossetto calls this product-led content, “where the product is front and center, is actively used to illustrate a point [and] show the reader how to do something that relates to the specific goal they came to your website for in the first place.”

There’s nothing inherently wrong with involving your product if it’s in the reader’s interest. It’s the dishonest bait-and-switch that creates frustration—smuggling a product CTA into an ostensibly “informational” article.

Set expectations from the outset: make the product connection obvious in the title (“How to do X with Zapier”), reiterate the benefit this product inclusion has to the reader, get to product references early in the article—and let the reader make an informed decision.

2. Descriptive Writing

“Quickly simplify collaborative internal processes by regularly benchmarking results, seamlessly integrating the findings along the way by leveraging the expertise of—and getting buy-in from—management.”

Some blog posts are capable of an impressive magic trick: it’s possible to read hundreds of words of text without ever learning anything. We call this “descriptive writing” (like descriptive statistics): reductive summaries of information that are technically accurate but don’t help the reader actually do anything.

This lack of specificity is the result of trying to write around knowledge gaps instead of addressing them head-on. This is often not deliberate: we don’t know what we don’t know. It’s hard for a content marketer to pinpoint vague or unclear language when they don’t know the subject matter inside and out.

But it’s easier for the reader to spot, thanks to tell-tale signs like:

Weasel words. When a writer is trying to explain something that they don’t fully understand, they often fall back on vague, hand-waving language like “retention problems” instead of talking concretely about “absenteeism, pay gaps, and employee churn.”

Idioms. As Gail Marie, our Director of Quality, explains, “if you beat around the bush because you’re caught between a rock and a hard place, your attempt at cutting corners will send the reader on a wild goose chase for meaning.”

Jargon. When used correctly, jargon can be a useful signifier, a way to demonstrate deep understanding of the subject matter—but jargon is rarely used correctly. Unnatural, belabored, and overused references can obscure the meaning of writing and make the writer look like a try-hard fraudster.

Even if the writer can spot these vagueries, there’s often a good reason to leave them in situ: they don’t want to get anything wrong. Writing for a “VC-backed startup founder” or “recruiting lead with 10+ years of experience” is intimidating, especially when we’re writing about subjects near and dear to their heart. Descriptive content might not teach them anything new, but it won’t provoke their ire either.

There’s only one way to replace the tell-tale signs of descriptive content: research.

Ask Why, Five Times

Descriptive content can usually be chased away by repeatedly asking yourself, “why?” (I like the five-whys technique).

Take a weasely sentence like: “Adopting an applicant tracking system can improve hiring outcomes.” With a bit of introspection and knowledge of hiring processes, asking “why does it improve hiring outcomes?” helps you unpack vague language into concrete benefits like “hire candidates faster” or “build a predictable candidate pipeline,” which can, in turn, be unpacked into specific actions: “hire candidates faster by tracking average time-to-hire and generating automated reminders to follow-up with candidates.”

(If you can’t unpack your weasel words into something more concrete, well—you’ll just need to learn more about your subject matter.)

Spend More Time on “How”

Some articles create more questions than they answer. They wax lyrical about “why data teams should conduct high-quality post-mortems” while sharing almost nothing on the nuts-and-bolts of how to conduct a high-quality post-mortem. They tell you to “ask the right questions” without providing the actual questions to ask. They end up being 80% “why” and only 20% “how.”

The “why” of any topic is easy for a content marketer to understand; the “how” is much harder, requiring detailed research. If left on autopilot, most of us default to writing about the thing we best understand.

Often, having this recognition is enough to turn off autopilot and refocus your writing. Include a small amount of context and justification on the “why” of your article, and focus the majority of your time, energy, and word count on the concrete tips, frameworks, and processes required to actually do the thing.

3. Deference to Data

“According to research from the Business Institute, 38% of SMBs say their sales process is too complicated. But according to a study from HBR, only 12% of those companies plan to implement a CRM.”

The idea that content marketing should be data-driven is a universally accepted idea, but the way in which most writers use evidence to support their writing actually undermines their argument. Instead of building an argument on a solid basis of evidence, statistics and quotes are often used as replacements for actual argument and persuasion, tacked on to a nearly-finished draft to add a veneer of credibility.

Take these common scenarios by way of example:

A tired-out statistic is injected into an opening sentence, and instead of piquing the reader’s interest, it sends them into snooze mode almost instantly.

Evidence for claims is offered in the form of data points that, when investigated, lead the reader to a questionable benchmark report from 2012 or—more likely—on a circular route of self-referencing blog posts that never actually pin down the source.

Quotes from subject matter experts are dumped onto a page with the thinnest narrative thread to connect them together, while the hard work of understanding the argument is left to the reader (our Director of Quality Gail calls this an “SME jamboree”).

The end result is content that bears all the hallmarks of research—seemingly surprising statistics, clearly cited claims, quotes from people with relevant credentials—without managing to persuade the reader that the conclusions drawn from the research are worthwhile. Evidence-gathering is reduced to a paint-by-numbers exercise.

Follow Where the Data Leads

This happens because data is usually used retroactively: the writer begins with a preconceived idea, and evidence is found to back it up. The writer latches onto anything that will support their argument, regardless of the quality or validity, and any data that seems to disprove their hypothesis is ignored.

This may feel like a natural consequence of content marketing—we’re writing content to achieve a particular outcome, that of supporting our business—but we can achieve the same end state in a much more persuasive way.

Research should not be a late-stage crutch to help defend a preconceived argument; it should be the process by which ideas are created in the first place (I love this quote from How to Take Smart Notes by Sonke Ahrens: “If insight becomes a threat to your academic or writing success, you are doing it wrong”).

In practice, that means making research a core part of your ideation process and ditching ideas if the evidence doesn’t support them. If the data has to be contorted and massaged to support your argument, chances are it won’t be persuasive anyway.

Use Persuasive Writing Techniques

If an article is well-written—that is, it’s logically coherent, exhaustive, and detailed—it should be compelling without mountains of statistics and benchmarks. Data should function as the reinforcement to a sound idea and not carry the entire weight of the argument; it should support your argument, not be the argument.

In fact, writers have a whole persuasion toolkit at their disposal, including frameworks like:

MECE: cover your topic in a structured, logical way, ensuring that your key points are mutually exclusive but collectively exhaustive.

BLUF: articulate your argument in the clearest, most direct terms possible, and lead with the bottom line upfront.

TAS: lead the reader on a persuasive journey from their currently held belief (thesis), through your criticism (antithesis), before landing at a new, helpful conclusion (synthesis).

4. Naivety

“Twitter achieved stellar growth in their first few quarters in operation, but never pinpointed why. CEO Jack Dorsey made multiple mistakes, chief of which was never understanding why people kept coming back to the product.”

Content marketers are not subject matter experts (at least in anything beyond content marketing). Nor should they be—true expertise is the result of years of immersion and experience. There’s a limit to how many disciplines a content marketer can master, and it’s unlikely to extend to topics as diverse as telecoms, financial modeling, and delivery logistics.

While there’s nothing inherently wrong with this lack of subject matter expertise—it’s why research and interviewing exist—problems do arise when those marketers forget and try to tell real experts how to do their jobs. This is almost always accidental (the writer doesn’t actually think they know best), but the end result is writing that reeks of naivety.

This naivety manifests in two main ways:

Armchair criticism. As content marketers, we are insulated from the real world. When we write about “launching a new product” or “improving profit margins,” we don’t actually have to deal with the problems of launching products or tightening up our company financials, so it becomes very easy to criticize others or point out obvious problems—but these problems only seem obvious because we’ve never had to solve them. Take the quote that opens this section: how many people on earth have the experience needed to offer a meaningful critique of the business nous of multiple-public-company-founding Jack Dorsey?

Making the obvious seem profound. The first step of writing about a new topic is learning about a new topic, but most writers leave the evidence of this learning process writ large on the page. They marvel at the new ideas they’ve learned and—understandably—make them the focal point of their writing, despite the fact that these new-to-you ideas are obvious and cliché to the expert reader.

Recognizing this phenomenon is a useful first step towards banishing naivety, but beyond that, writers can also:

Get (A Little) Skin in the Game

Though we can’t often become experts in our subject matter, we can usually find some small way to actually experience the thing we’re writing about.

This doesn’t need to be complicated. For an article about paid advertising, you can gain useful primary experience with a $5 budget for Facebook ads, getting exposure to the tools and interfaces—and decisions and trade-offs—faced by your reader every day. If you’re describing how to set up a CRM for a small business, there’s no substitute for starting a free trial and getting hands-on with the product.

Even secondary research, like asking someone from your finance team to walk through their daily workflow, or share some of the problems they wrestle with each day, is usually enough to reveal the iceberg of complications hidden beneath the surface of the “obvious” problem you’re trying to solve with your article.

Understand in Your First Draft, Synthesize in Your Second

A first draft is a useful place to collect relevant information and begin the task of understanding your subject matter, but many writers stop there. This type of content is useful to you, the writer, and any readers new to the topic, but it offers nothing new or interesting to somebody already well-versed in the subject matter.

The harder, better thing is to use your second draft to synthesize that information: to take facts, figures, and basic principles, and connect them together in a coherent narrative, a defensible opinion, a new idea, or a logical next step (Jimmy Daly talks about this as the difference between writer-centric and reader-centric drafts).

Banish Bad Content (While You Can)

These problems usually stem from tight deadlines, rigid publishing schedules, and a sense that content marketing should look and feel a certain way, with a certain word count or a certain number of calls-to-action. Content marketing needs to drive sales, and the most obvious way to signal helpfulness toward that goal is write more, publish faster, and mention your free trial every few paragraphs.

And content can work in spite of these issues. Sometimes, a problem is so big and so painful that you’ll embrace help from any source—no matter how salesy or insincere. But even if business comes from these interactions, the results are a fraction of what could be if content marketing was more honest, more subtle, and less salesy.

Every passing day, your readers’ tolerance for shallow, insincere content marketing wanes. There is more choice—of brands, products, blogs, and articles—than ever before. Like a car dealership staffed by slimy salespeople, it’s becoming easier than ever to sail past salesy blogs and get the information needed somewhere else—somewhere that makes them feel a little less sold-to, patronised, or misled.