The blank page syndrome. We all know it, we’ve all been there.

You stare at your screen, and you don’t know how to begin.

Staring becomes procrastination. Procrastination becomes anxiety, and it’s all downhill from there. The Blank Page is the blockiest of writer’s blocks.

But now, there’s a better way, an escape from this dreaded state. An instant, effortless fix that Professor Ethan Mollick calls:

The Button.

The Great Seducer: The Button

“Students are going to use it to start essays. Managers will use it to start emails, reports, or documents. Teachers will use it when providing feedback. Scientists will use it to write grants. Concept artists will use it for their first draft. Everyone is going to use The Button.”Ethan Mollick in Co-Intelligence

We suffer from blank page syndrome for a reason: it’s the moment of our hardest thinking. It’s where we make high-stakes decisions about our topic and thesis, where we choose from an infinite number of possibilities.

And then, right in that moment, when we’re vulnerable and doubtful, generative AI enters the scene, disguised as The Button.

“Just click me,” it whispers, “and I’ll solve all your problems.”

“I’ll get you started”

The Button’s masterstroke is getting your page from zero to one — instantly.

Here’s one of countless examples you find all over the internet. In this case, a product manager on X praises AI for removing that intimidating nothingness: “Automating the shitty first draft stage with tools like ChatGPT instantly brings your thinking up a level so you can concentrate on the important stuff.”

The takeaway here is that putting something on the page gets you from staring to starting — a trick writers have used for decades.People have been writing “shitty first drafts” ever since Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird came out in 1994. And in 1992, author and poet Charles Bukowski suggested, “Writing about a writer’s block is better than not writing at all.”

The Button achieves all this for you in a split second, even with a nothing prompt lacking any original thought.

“I’ll do the hard work for you”

This ploy goes something like this:

I’ll take care of the blank page for you.

That reduces your cognitive load.

You’ll have more energy and creativity left to refine and finish your piece.

These steps then repeat themselves throughout your writing process. AI handles the mundane stuff, so you can focus on the more high-value work.

There’s some truth to this idea. Research from Jakob Nielsen, a renowned usability expert, suggests that: “Without AI, less-skilled users’ creativity is repressed by their need to devote most of their working memory to data handling. But, with AI, their brains are freed up to be more creative.”

“I’ll make you more creative”

In this third variation, The Button presents itself as a creative stimulant.

Computer-generated ideas trigger your creativity, so you come up with better ideas. You feed those back to the AI, which returns even better ideas — and on and on this flywheel goes.

A study featured in the Harvard Business Review (HBR) supports this approach. Participants produced more original ideas after first seeing AI-generated images that inspired them.

The HBR study used Stable Diffusion to generate generic designs of crab-inspired toys. They then used these AI-generated images to develop ideas for actual products. The authors propose that the strangeness often present in AI art might stimulate creative thinking. (Image source: HBR )

The Dangers of Outsourcing Your Thinking

Imagine I offered you a robot that goes to the gym for you. Would you want it?

Read that sentence again, then consider The Button.

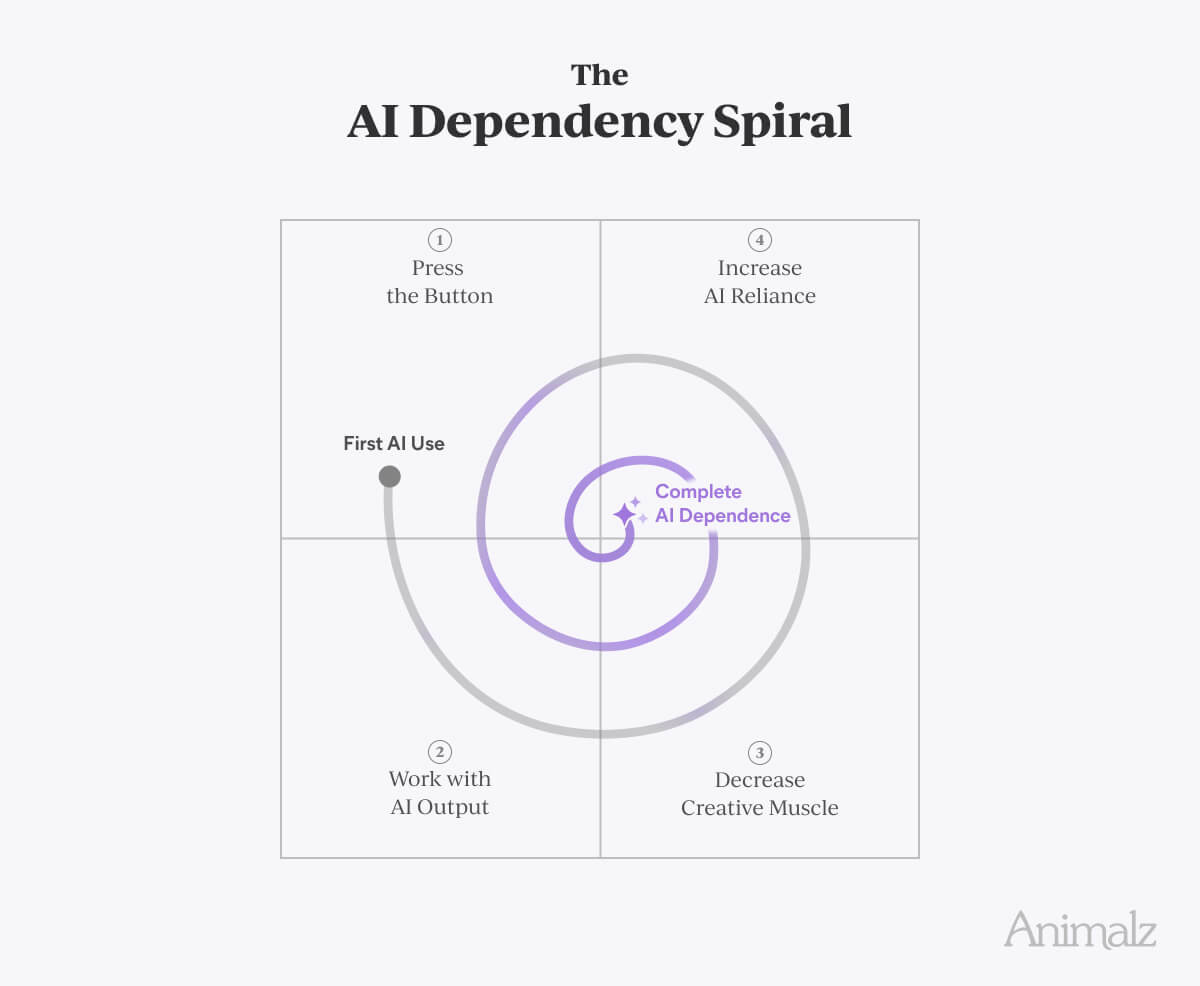

When you press The Button, you delegate the act of writing. And if writing = thinking, who does the thinking when AI does all the writing?

Pressing The Button is the intellectual equivalent of sending a robot to the gym.

You Stop Thinking

When you stop writing, you stop thinking. Your mind becomes lazy. And I say that from personal experience.

I’ve had several periods where I tried to let AI do my writing. To be fair, the writing of recent models like Anthropic’s Claude is impressive and will only improve. But my brain stopped working. My ideas became a trickle, I fell for hallucinations, and I started relying on AI for even the easiest of sentences.

I’m not alone. In Co-Intelligence, Professor Mollick cites research that recruiters who are given higher-quality AI to assist with their work perform worse than those using lower-quality AI: “When the AI is very good, humans have no reason to work hard and pay attention. They let the AI take over instead of using it as a tool.”

The researchers called this phenomenon “falling asleep at the wheel.” I call it the “Google Mapification” of your mind.

Like with a GPS, you start relying on it for directions all the time, even in places where you know the way. You end up taking routes you would know are wrong and, over time, completely lose your natural sense of direction because you don’t use that part of your brain — it’s outsourced to the GPS.

Curious what content like this costs? 💰️ Get this article’s price breakdown to know what you’d pay for something similar. Get the breakdown We never send you spam or share your email address with third parties.

You Anchor to Suboptimal Ideas

Psychology gave us “anchoring bias.” When presented with an initial number, word, or answer, our minds cling to it. Even when we’re aware of this flaw, it still happens; the initial anchor taints everything that follows.

A similar concept exists in creative work: “design fixation.” You fall in love with an idea and that love blinds you to other possibilities.

The Button triggers these problems when it fills the blank page for you. It spits out ideas and, with a bit of algorithmic luck, some of them will be good.

You’re still trying to think — because you read this article 😊 — but the better AI-generated options anchor your mind. You might even get fixated on one of them, limiting the possibilities you can imagine.

You end up with a suboptimal idea, oblivious to the more original concepts you might have discovered without AI’s anchoring.

You Become Too Efficient

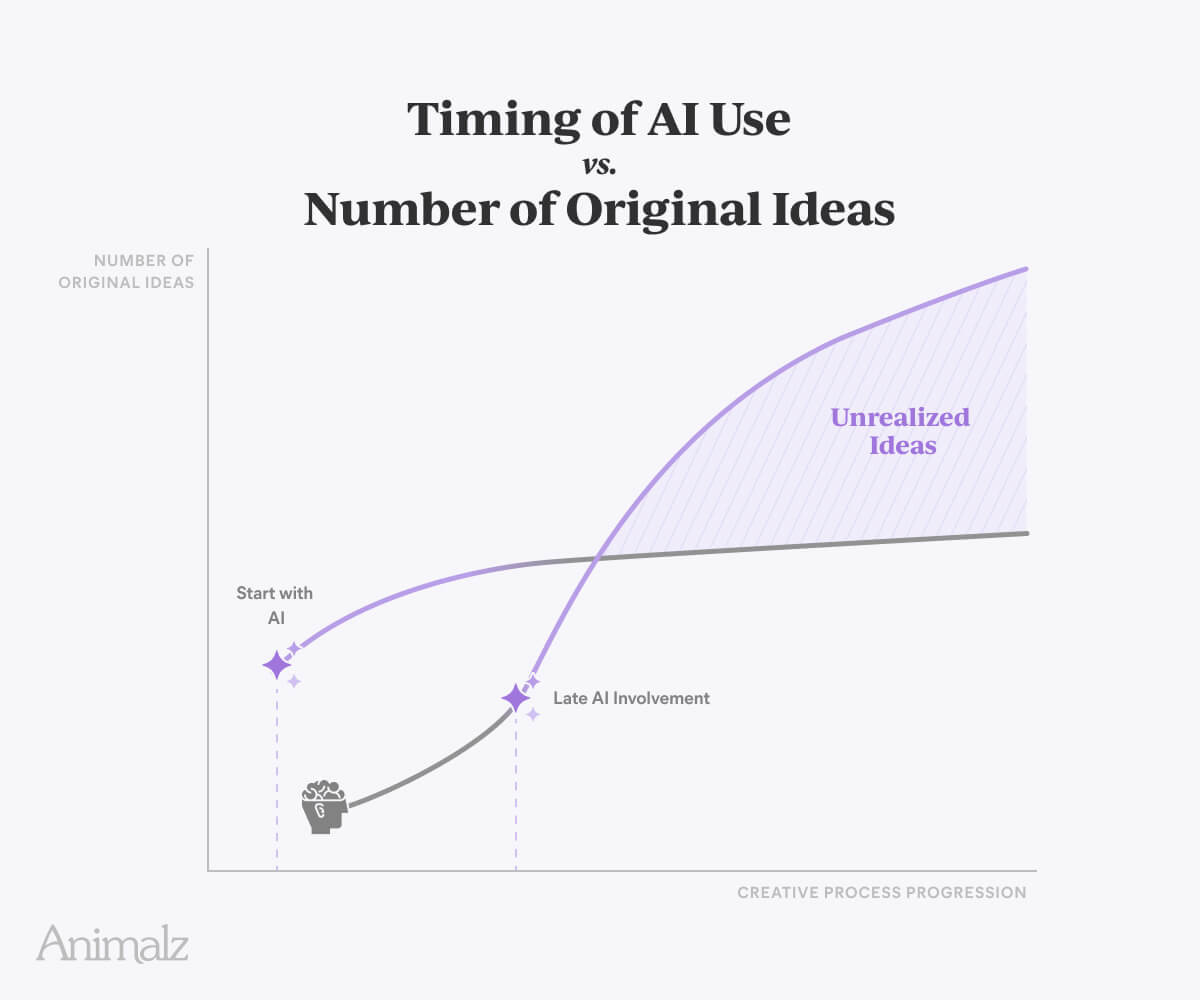

Paul Graham observed that writers usually “discover new things in the process of writing.” That’s exactly how his insight ended up here.

While working on this piece, I recalled a Farnam Street article about first ideas never being your best. I found it, read it, and came across the connection between writing and thinking, leading me to Graham’s quote.

Had I used AI, I would have sped past this insight entirely.

Anne Lamott, mentioned earlier, makes a similar point in Bird by Bird. She essentially says we have to write a lot to get to the writing we’re after: “You needed to write to get to that fourth page, to get to that one long paragraph that was what you had in mind when you started, only you didn’t know that.”

AI short circuits the serendipity that leads to your best ideas.

Write With AI Without Losing Yourself

“Human beings need to build A.I., and build the workflows and office environments around it, in ways that don’t overwhelm and distract and diminish us. We failed that test with the internet. Let’s not fail it with A.I.”Ezra Klein in “Beyond the ‘Matrix’ Theory of the Human Mind

I’m not here to tell you AI is bad and you must hide from it in a cabin in the woods. But you do need some practices that protect your human creativity throughout the writing process.

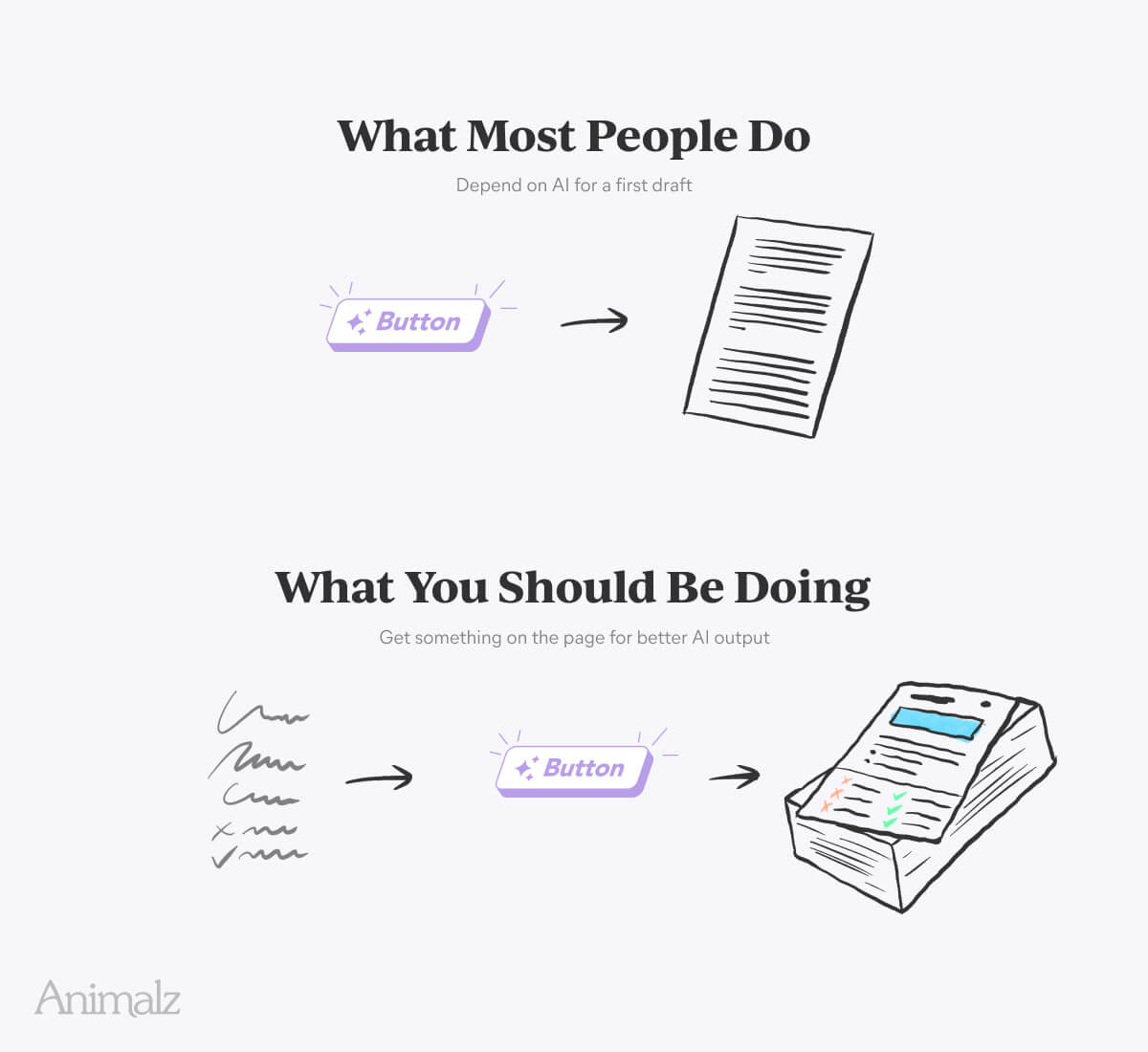

Always Start With Your Input

Here’s another writer praising ChatGPT, this time on Reddit: “This tool can possibly be the cure for writer’s block.” They’re writing a fictional story and seem to use AI in the same way as the product manager quoted before — to fill the blank page.

When you look closer, this person actually provides ChatGPT with a lot of input: a main character who has a girlfriend, an accident, and a job as a detective. They seed the algorithm with their own ideas before pressing The Button.

This approach is the most important takeaway from this article: get something on the page before pressing The Button instead of pressing The Button to get something on the page.

Good input is better than bad, and bad input is better than nothing. Even a hint of an original idea takes the AI away from digital landscapes in today’s world featuring chefs in kitchens stirring up mediocre metaphors. (Puzzled by that sentence? Congratulations, you likely haven’t spent much time reading or creating AI-generated texts. 🤝)

Your input doesn’t even have to be text. It can be an article brief, a mindmap, a sketch, a mood board, a stream of consciousness, a voice memo, an interview, a meeting recording, an outline — anything but nothing.

Let AI Get You Unstuck

When I was writing about pre-mortem meetings for a customer, I had a hunch some concept from Buddhism could make a good hook. Without AI, I might not have figured it out, or it would have taken an unreasonable amount of time.

ChatGPT nailed it instantly based on a vague sentence not so different from the one in the previous paragraph. We went on to create an intro I could have never written without AI, and AI could have never written without me.

This example shows again that a human seed — even a vague one — steers the AI away from chefs and gardeners, its favorite metaphors. But it also demonstrates how the algorithm can get you unstuck.

It can finish your half-formed idea like it did for me. It can connect the dots between disjointed sections in a story or give you twenty variations of a sentence that doesn’t feel right.

Ban AI at Beginnings

This has happened to me many times: I spent hours writing with AI and started over-relying on it. Tired, at the end of my day, I read my draft, feel good about it, and go to bed.

The next day, my morning brain checks that same text and exclaims: “It’s crap!” The draft drowns in weasel words and other descriptive writing, saying too little with too many words.

AI can seduce you with its smooth talking and taint your judgment, just like it did with the recruiters we met earlier. You must carve out moments throughout your writing process that pull you away from its charms.

The most effective way to do this — and remember doing it — is to ban AI at beginnings: when you stare at a blank page, when you start your research, when you structure a new section.

At each stage of your work, give yourself time to think deeply and struggle with the problem — it’s where original ideas are born. Only after you’ve wrestled with your thoughts and written them down, call in AI assistance.

The Value of Your Thoughts Will Only Increase

“My first thought is never my best thought. My first thought is always someone else’s; it’s always what I’ve already heard about the subject, always the conventional wisdom. It’s only by concentrating, sticking to the question, being patient, letting all the parts of my mind come into play, that I arrive at an original idea.”William Deresiewicz in Solitude and Leadership

In today’s digital landscape, where The Button seduces ever more writers to use words like these, the value of thinking and original ideas increases.

So stay strong.

Don’t send robots to the gym.Resist The Button’s temptations.Keep using your mind.

Your human creativity is — and will continue to be — your greatest asset.

Curious what content like this costs? 💰️ Get this article’s price breakdown to know what you’d pay for something similar. Get the breakdown We never send you spam or share your email address with third parties.