Blindfold a dozen marketers. Ask them to describe the guiding principles of a case study. You’ll hear the same answers again and again.

Make the customer the hero of the story. Follow a recognizable format — something like problem, solution, results. Back up your claims with evidence, be it a quote, data point, or anecdote.

So why are persuasive, wallet-opening case studies so darned rare?

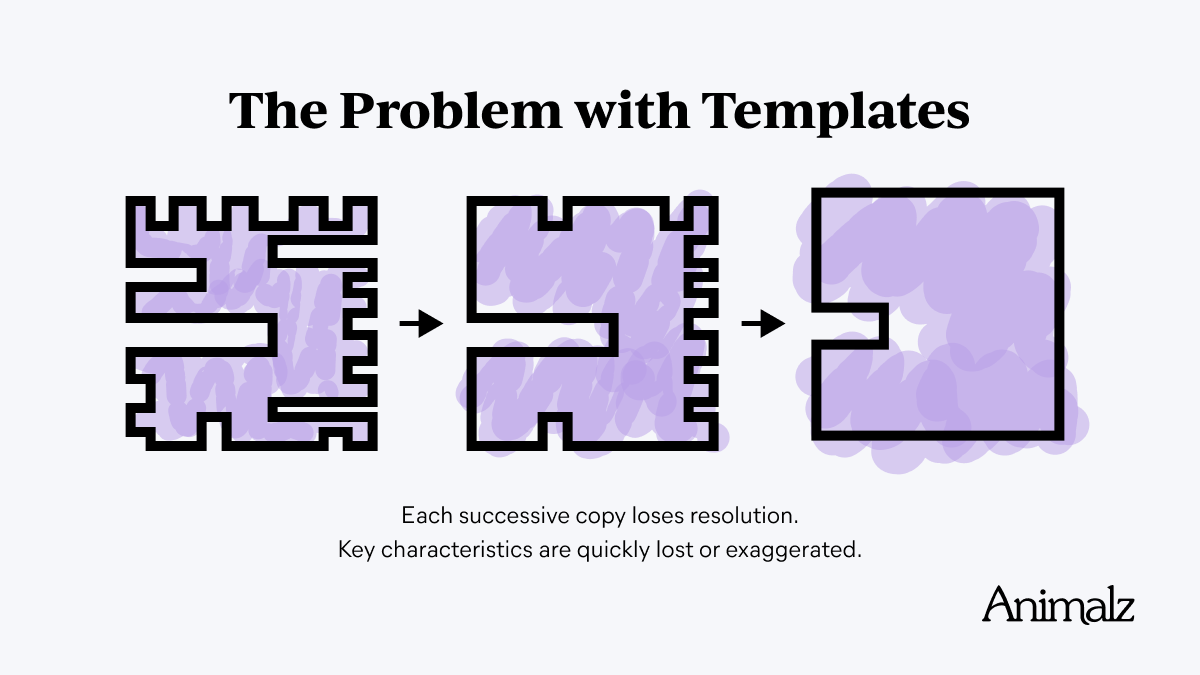

Case studies are one of the most widely templated types of content in existence. But following a template usually comes at the expense of thinking from first principles.

Most marketers create things that look like case studies instead of things that help close deals. They follow the “best practices” even when they’ve stopped being useful:

It’s good to focus on the customer’s story…but it’s bad to make yourself completely absent from the narrative.

It’s good to use a recognizable structure and signal to the reader that “this is a case study,”…but it’s bad to reduce every story to the same generic writing-by-numbers format.

It’s good to offer supporting evidence…but it’s bad to rely on contextless percentage increases as your sole means of persuasion.

Here are five advanced ways to improve the persuasiveness of your next customer case study:

1. Separate the Generalizable From the Situational

Most case studies fail because the story they tell feels situational — it applies to one company, at one moment in time, and can’t offer anything useful for a different company.

After all, a case study is typically a sample size of one — and a sample size of one should always be treated with skepticism.

It’s the author’s job to persuade the reader that the one-off experience explored in a case study contains useful lessons that can be implemented at another company. They need to extrapolate a generalizable framework from a single story and prove to the reader that they understand, in intimate detail, the unique challenges faced by the reader’s specific type of business.

In practice, that means explicitly addressing questions like:

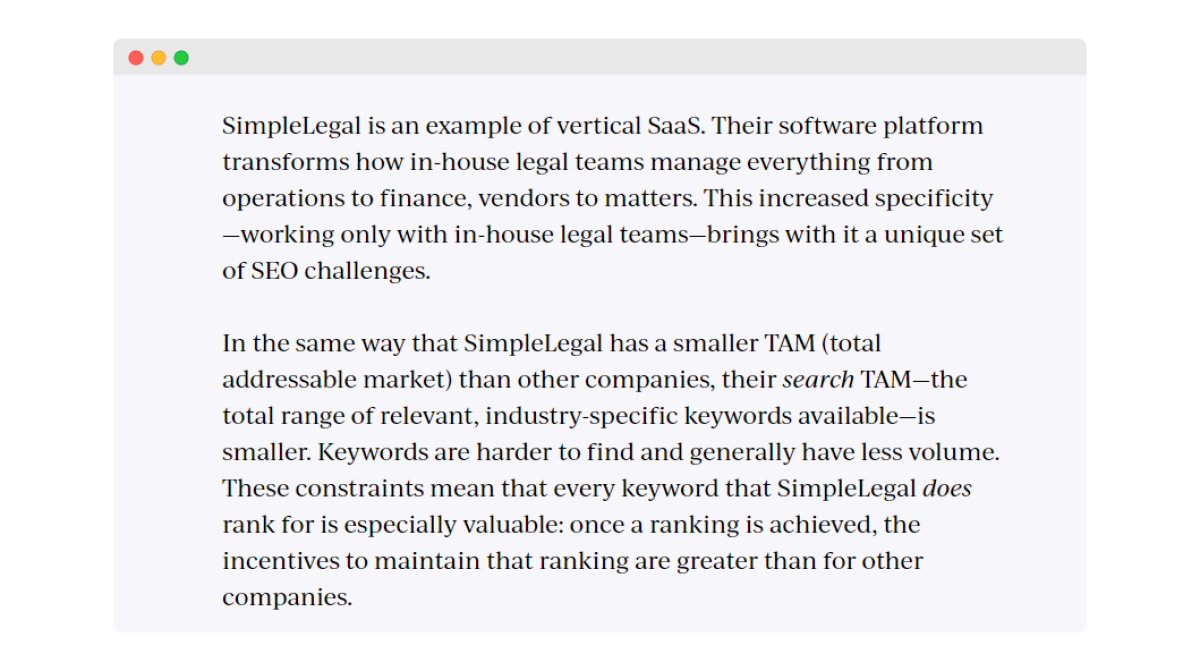

What is the business model that underlies this single company? (e.g., vertical SaaS)

What are the unique challenges created by that business model? (e.g., a relatively small pool of relevant keywords)

What steps did you take to overcome those challenges? (e.g., dedicating greater-than-ordinary resources to content refreshing)

In other words, showing your success isn’t enough — you also need to show your workings and explicitly prove to the reader that your success wasn’t a fluke.

2. Treat Yourself With Respect

The customer is the hero in your case study, and you are the sidekick — but sidekicks still matter.

Businesses are only made possible by the customers that support them, and it’s a common (and valid) truism that case studies should make your customer look good. This is, after all, their story more than it is yours.

But many companies take this guiding principle too far and erase their ideas and actions from the narrative. You might not be the hero, but you should still have a visible role in the story.

You are experts, and your experience and decision-making were integral to whatever positive outcome the customer achieved. Your job is to position yourself as the enabler of another company’s success and not as just a bystander.

This may feel like a fine line to tread — treating yourself with respect while avoiding immodesty — but there are plenty of ways to make yourself an active participant in your case study:

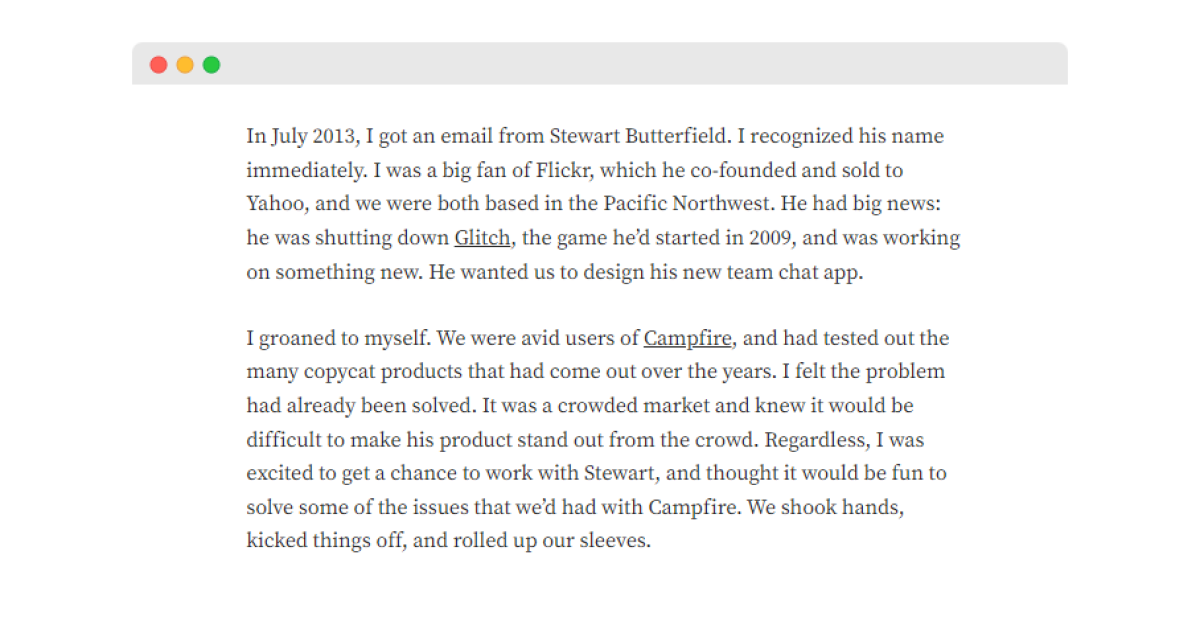

Surface your thought process. Bring the reader on a journey through the questions you asked, the decisions you made, the lightbulb moments, and the mistakes that served your successful outcome.

Embrace humility. Share the mistakes and dead-ends. What surprised you about the situation? What did you get wrong?

Position yourself as a peer, not a subordinate. Highlight moments of pushback and conflict where your expertise was rightfully at odds with the customer, and prove that you weren’t simply an order-taker.

In that vein, whilst it’s great — essential, even — to include the customer’s voice, perspectives, and ideas in your case study, it’s a mistake to base your case study solely on their narrative. Things don’t always happen for the reason customers think, and your case study needs to serve a particular outcome (convincing someone to buy your product).

Don’t shy away from challenging the customer’s narrative — just don’t surprise them with a left-field framing on publication day.

3. Support Your Narrative With Data (Not Vice Versa)

Case studies are rife with a phenomenon we call “data deference”: relying on contextless statistics and percentage increases as your sole means of persuasion. When every case study touts a “100x” increase, readers become so inured to inflated statistics that most simply gloss over big percentage increases.

There are a few ways around this problem. When you want to feature data, don’t shy away from smaller, more “realistic” statistics — they’re often more persuasive. As any decent marketer knows, a 5% compound monthly growth rate is a big deal.

And whilst cold, hard performance data is great, so are stories of challenges faced and problems solved, anxieties confronted and lessons learned. Not every worthwhile success story will have amazing data to accompany it — so don’t limit yourself to just “data-driven” case studies.

Paraphrasing advice I got from Walter, Animalz’s chairman: “We won for a customer. I think that’s pretty amazing.”

4. Editorialize the Narrative (And Ditch the Boring Stuff)

A case study shouldn’t be a blow-by-blow account of every action that went into a successful relationship.

Many case studies suffer from a lack of editorial judgment — the willingness and ability to sift through everything that happened to find the handful of actions that had the greatest impact and, crucially, help tell a coherent and useful story. Whilst technically, yes, your customer did import all of their data from a rival platform, there’s no need to cover the minutiae of the import unless it matters to the outcome you achieved.

There’s a tendency to assume that case studies have a captive audience — they’re a necessary part of many buying processes, so prospects have to read them. Even if that is true — wouldn’t it be better if your case study, amongst all others, was actually interesting?

This “editorializing” doesn’t need to be complicated:

Focus on the two to three ideas, actions, or stories that you find most interesting or counterintuitive.

Reference important-but-not-interesting ideas in a sentence or two.

Assume the reader is smart enough to fill in some obvious gaps, and don’t feel the need to tirelessly explicate every idea and concept.

5. Be Wary of Post Hoc Narratives

The final bar to clear is a big one: most case studies are really post hoc rationalizations that don’t reflect the actual decisions or actions that led to success.

There’s a quote from The Lords of Strategy that I love. In response to the prevalence of business cases — a common business school format for understanding how successful companies became successful — the author writes:

“Is that what the company thought it was doing? Did it know that it was performing this alleged act of strategy?”

Case studies generally have the same problem. They sit at the intersection between analytical tools (for understanding why something happened) and marketing tools (for helping to sell your product or service). We should be happy to accept some over-simplifications for the purpose of clarity and persuasion, but not at the expense of offering useful, practical advice for companies in similar situations.

If you extract yourself, and your company, from a case study, it should still offer something innately valuable to the reader: a lesson learned, a framework to apply, a process to use. Connect the events back to some larger, generalizable “thing” that the reader can use to their advantage. The payoff needs to be more than “wow, this company is smart!”

Here’s a good acid test: when the customer reads the case study, it should feel like a heroic-but-recognizable representation of what they did and how they thought. It should be them, on their best day — and not a completely alien story.