Here’s the pageview paradox: many of the things that we do to improve our marketing metrics actually hinder long-term business growth.

This happens through two mechanisms. The actions we take to increase our performance metrics also serve to quietly, almost invisibly, frustrate potential customers, and because of our fixation on concrete measurement, we also overlook lots of opportunities to deliver value because they don’t increase our metrics.

This is not to say that performance metrics are useless — only that there are unintended consequences to their measurement that need to be kept in check. They offer false certainty, painting a rosy picture of the now while simultaneously making the future a little bit harder.

The Problem with Proxies

This problem is fundamentally one of proxies.

Everything we do as marketers is designed to generate new business for our companies. And there are, obviously, many prerequisites to an anonymous stranger becoming a customer. They need to discover your company. When a problem appears, they have to trust your ability to solve it. They require a preference for your company over others that offer similar solutions.

Many of these milestones are hard to measure: they happen inside people’s heads or in spaces that we can’t easily reach, like private DMs and email chains. But that doesn’t stop us from trying to measure them.

The marketing metrics we use, like pageviews, are proxies. It’s hard to measure nebulous things like “increasing trust” or the “spread of ideas” and easier to measure the number of people who click a blog post or the time they spend looking at a page. We hope that metrics like pageviews correlate with the actual thing we want to measure, so we use pageviews as a stand-in for the real data.

Proxies are generally useful things. The ability to approximate hard-to-measure things from easy-to-measure things is helpful — and a metric like pageviews can be helpful: more pageviews each month is, in many cases, a good thing, usually representing more people spending more time with your company. More pageviews probably mean more of the things that matter.

But problems arise when our proxy stops serving our actual goal; when the pursuit of metrics stops helping our ability to deliver value and build trust and actually begins to undermine it.

That happens more than you’d expect.

How Performance Metrics Punish People

Left unchecked, the pursuit of metrics makes marketing adversarial.

A core goal for any marketer is generating value for potential customers, but performance metrics introduce a caveat into the equation: generate value in ways and places where we can measure it.

They change our behavior and create an incentive to share just enough value through ad copy, tweets, and email teasers to cajole the reader to click through to our website — somewhere where their actions can be recorded. But the reader just wants the payoff. They would be happier to get the value right here, on their terms, in whatever space they’ve chosen.

This plays out across most metrics:

In service of pageviews, we frustrate readers by funneling them to our attributable URLs and away from the places they want to be: on social media, in community Slacks and Discords, or in their emails.

In service of conversions, we tease the value of ebooks and resources, only to bait and switch the reader by hiding them behind email gates.

In service of time-on-page, we build ever-longer skyscraper content instead of BLUFing the answer right there in the intro text.

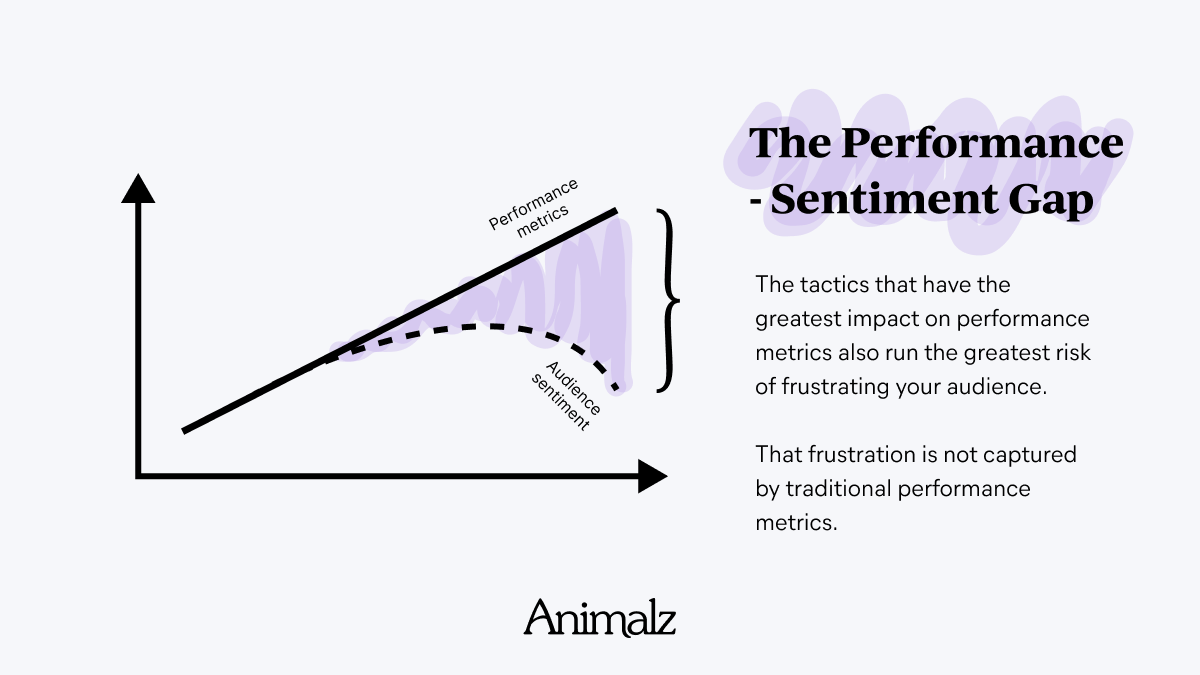

Through the lens of performance metrics, these look like solid choices — but the harm they cause is invisible. We don’t see the frustration and quiet resentment we create: we see only the upward line on our performance graphs. These decisions are optimized for the proxy — gaming the metrics — and not the outcome we really want — building trust and affinity.

How Performance Metrics Blind You to Better Opportunities

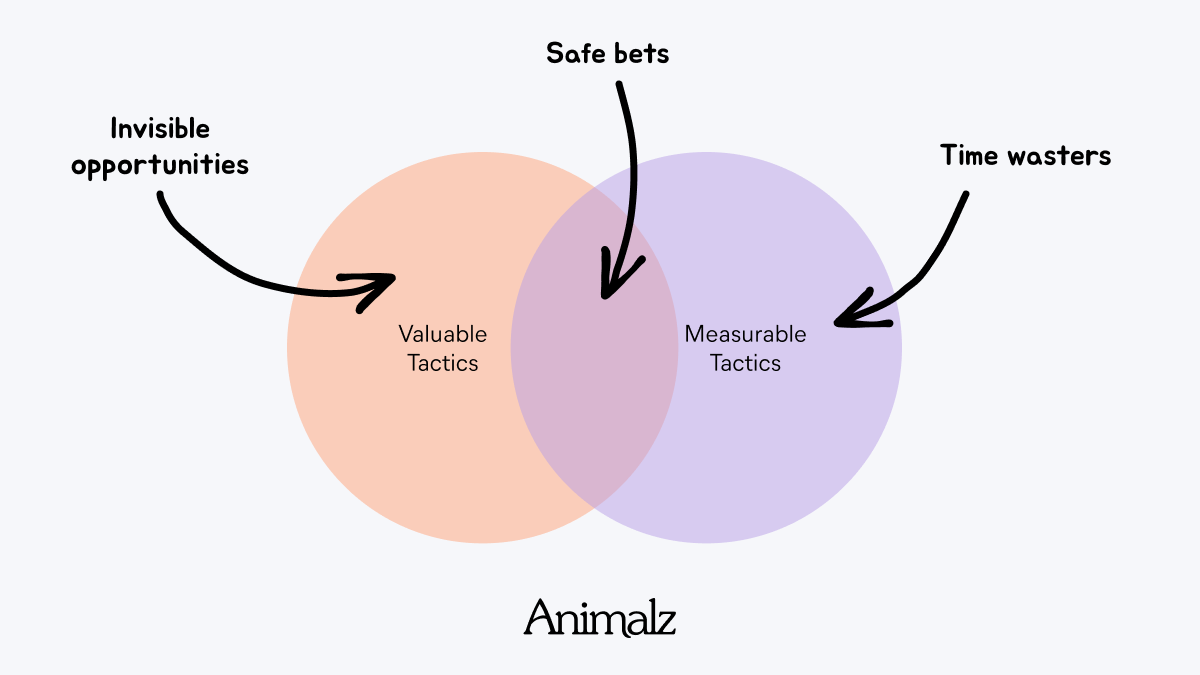

In a similar vein, many worthwhile marketing opportunities appear invisible through the lens of traditional performance metrics.

The last decade has seen a huge fragmentation of online spaces. Company blogs have slipped further down the list of places where people hang out, with online communities, fora, and social networks growing in importance.

Despite that, our performance metrics are still biased toward the spaces we control. We have chosen the convenience and false confidence of readily available data at the expense of meeting people where they already are:

We overlook opportunities to deliver platform-native value (what Amanda Natividad calls zero-click content) — in tweetstorms, communities, email threads — because it won’t be reflected in our pageviews.

We focus all of our energy on creating new ideas and new articles at the expense of revisiting existing ideas and ensuring they actually stick.

We avoid new platforms, like Substack or Discord, because we can’t “own” our audience.

In each case, we’re using data from an old world to inform our decisions in the new, and it’s nudging us further away from the one thing that actually matters: delivering value to potential customers.

The False Certainty of Metrics

Here’s the thing: every marketer I know understands that metrics are proxies, imperfect analogs and not completely representative of the “things” that actually matter. But even if individuals understand the nuance, it rarely carries through into marketing strategy.

For one, big organizations need the false certainty offered by quantitative data. The bigger the organization, the harder it is to communicate nuance, and the more powerful concrete numbers are — no matter how flawed or nonsensical those numbers may actually be. Tie performance metrics to compensation and you further cement their status as goals to be achieved at all costs.

We also have our own cognitive biases to consider. Certainty is tempting, and analytics platforms sell certainty. Concrete numbers can temporarily assuage the doubt we feel about our marketing efforts. We know the data isn’t reflective of reality, not really — but the fiction is extremely tempting.

This is not to say that analytics platforms are trying to mislead us; just that both platform and user have an incentive to squint a little bit and treat their data points with more confidence than they deserve.

The end result is the same: our marketing functions as though performance metrics are the end and not the means. We optimize our decisions for visible results at the expense of the invisible ones.

Great Marketing Requires Faith

This is not an argument to ditch quantitative reporting. I still fill out a monthly reporting spreadsheet and will continue to do so because the data I collect is directionally useful. But this is an argument for changing how we think about and weight quantitative performance data.

Don’t shy away from interesting marketing plays just because you don’t — yet — have a decent way to measure their performance.

In fact, there is probably an inverse relationship here: the more measurable a particular marketing tactic or channel is, the less opportunity is present. The ability to justify a decision through concrete data means that other people can also justify (and act on) the same data. By the time something is measurable, the greatest opportunity may already be over.

The strategies and channels with the greatest promise are often the hardest to rationalize through the lens of common marketing metrics (just how does your media marketing strategy impact your MQL numbers? How many customers did that offsite podcast appearance generate?).

Marketing metrics are useful, but they are not a goal in their own right. Despite a growing abundance of data, great marketing still requires acts of faith.

So when you’re planning out your marketing campaign, filling in your content calendar, or workshopping your distribution strategy, ask yourself: are these pageviews coming at the reader’s expense?